The Crafty Bastards Story

Ripped from the Pages of Myth and Legend!

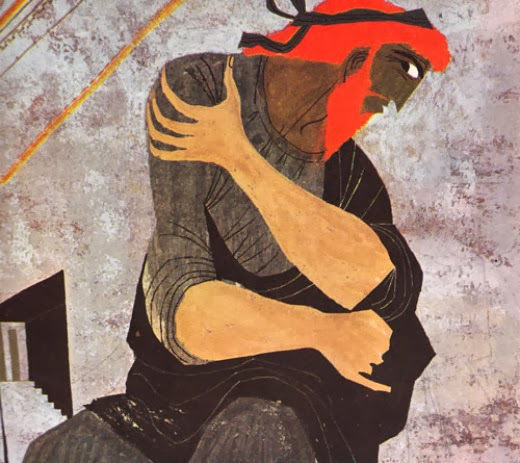

The Greeks, those great namers, had a word for it. Metis means wisdom, skill, craft, but it also suggests that wisdom and skill are strongest when crafty and cunning.

The Greeks, those great namers, had a word for it. Metis means wisdom, skill, craft, but it also suggests that wisdom and skill are strongest when crafty and cunning.

Crafty is from our own Old English cræftig, which means strong, powerful. The cue here tells us that real solutions are often crafty ones.

Yet crafty is a two-faced word. It has a sticky reputation of getting there through wiliness and ruse, trickery and deceit, by sly and artful guile. Guile itself hails from the Old Norse gel — trick or craft — also related to the Frankish wigila, or ruse, and our Old English wigle, or divination.

Cunning likewise shares the same strong provenance as crafty: From the Old Norse double root — kunna, for know, and cunne, for can — the origins of cunning speak right to the “can do” spirit. I know, therefore, I can. But I know, and I can, because of my cunning ways.

So craftiness is strength that comes from thinking different, and cunning is being able to do because you know what others do not. Ancient Greeks so much admired this quality that they gave their word for it to their greatest god [Zeus] and their most enduring hero [Odysseus]. Our Viking ancestors did no less. Metis, crafty, and cunning, were how we celebrated our heroes.

Not so anymore. Over the centuries, “crafty” and “cunning” have taken on heavy baggage. Today’s thinkers are not rewarded for being crafty and cunning. When Baldrick confides — “I have a cunning plan” — to Black Adder, we now laugh because this has become a very different cue. We know that what comes next will be sly, devious, and underhanded: The work of rogues, not heroes.

How did this transformation take root? We know some things.

The trickster figure inhabits every world mythology: As Loki, Eshu, Hermes, Prometheus, Inktomi, or the Coyote, the Raven, Reynard the Fox, or Bugs Bunny. The trickster can be male or female, or even change natures. Even the gods, like Zeus (or Metis herself) were born tricksters.

Why, for centuries past, did we so celebrate the trickster — and why no longer?

As humans emerged into History, they first created archetypes. Archetypes limned and lived those stories that tell us where we come from and who we are — and the stories stay with us.

Our first archetypes leapt out of the Iliad. But along with the pride, perfection, and pathos of mythic gods and heroes is always too the figure of the trickster. God or hero, the trickster is the rule-breaker, the iconoclast, the raiser of awareness, the holder of secret knowledge, the equalizer — above all, the trickster — because he (or she!) has special knowledge, but also, a special kind of intelligence.

Call it a special attitude.

But attitude is not magic. The archetypal trickster has no special powers, no access to secret knowledge unknown to others. Craft and cunning come solely by using information available to all — the trick is in being able to see what others cannot: Even when it stares them in the face.

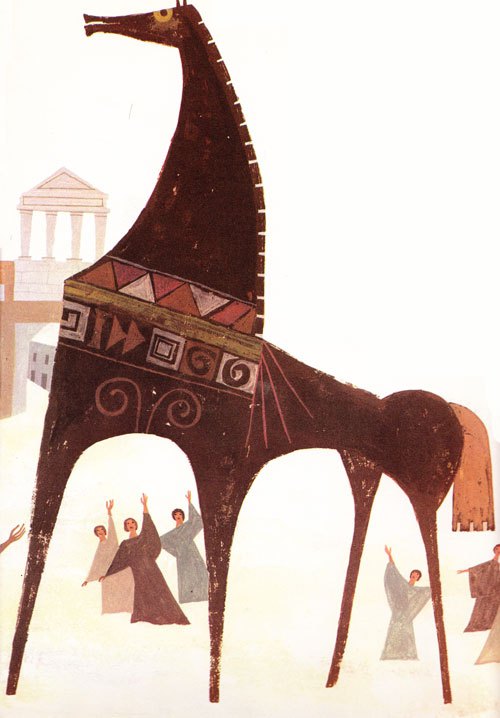

The great trickster of strategy and war was Odysseus. In Homer, Odysseus just plain does not think like everyone else — but he survives almost everything thrown at him, including the wrath of God (in his case, Poseidon).

In both Iliad and Odyssey, this man is a survivor. Penelope, his wife, is also one of the great tricksters. Together, they seem to transcend both fate and the gods.

Perhaps this is the real story of Furciferi Versuti — of the Crafty Bastards. Being able to mine the knowledge others cannot; being able to turn knowledge into insight; being able to translate insight into action, however cunning and crafty its execution.

Perhaps this is the real story of Furciferi Versuti — of the Crafty Bastards. Being able to mine the knowledge others cannot; being able to turn knowledge into insight; being able to translate insight into action, however cunning and crafty its execution.

No wonder this was the heroic cast our ancestors prized: Because it was a hard world out there, and the night held many terrors. Metis, the true weapon of the trickster, thus may well represent an evolutionary adaptation. Men and women best suited to survive — would insure their communities survived too.

We have come a long way from that world. Perhaps as Americans, with movie-triumphant history still ringing in our ears, believe ourselves beyond Maslow’s bottom rung. This shows in the thinking we value. We prize thinking that endorses our feelings of surety. Correct form and appearance is rewarded; alternative thinking is punished. The established order of things is the only credible reality; exploring change that might overturn it is taboo.

If Odysseus is no longer required in the Greek war council, it is because the order feels more threatened by his attitude than the possibility of defeat, now looming before the walls of Troy.

Clearly, the Greeks chose to embrace Odysseus rather than cast him out, because, after ten long years, they were staring imminent, actual defeat in the face. His metis broke the siege and won the war. Cunning was the path to victory.

Establishments that deny or punish different thinking, clearly, inhabit an irony-free state of mind in which existential  does not exist. In our pride today, we must think we have traveled very far indeed from those human communities that celebrated the trickster as their surest ticket to survival.

does not exist. In our pride today, we must think we have traveled very far indeed from those human communities that celebrated the trickster as their surest ticket to survival.

Furciferi Versuti thus celebrates not only the ancient legacy of the trickster, but also how the crafty thinking of metis is so easily cast aside in fat times: To be denied and impugned. Hence, our motto reminds that the surest way to proscribe those who think different is the oldest social stigma: Bastard. Above all, to be illegitimate is to exist outside the pale, even if — like Medieval Ireland — it is outside a palisade of wooden stakes demarcating a tyranny.

Ideas, like people, can be made illegitimate too — for a while. Yet new ideas, solutions to impossible problems, and even paths to survival do not tend to come from a complacent in-crowd. Rather, the way ahead comes from banished outsiders: From those who find insight, in plain sight.

This is the spirit, and the story, of Crafty Bastards.

Michael Vlahos, Furciferi Versuti “Grognard” (G.I.)

KGH Capability Statement

KGH Capability Statement